By Wells Winegar

The New Jersey Education Association has been in the headlines recently, not for its classroom accomplishments but for its spending habits—specifically, lawsuits from teachers contesting the nearly $50 million of member dues were funneled into the ill-fated gubernatorial campaign of its former president. Against that backdrop, I attended the NJEA’s annual convention in Atlantic City, hoping to see the organization’s focus shift back to professional excellence and academic outcomes. What I found instead was a gathering that seemed far more interested in politics, identity, and performance than in the craft of teaching.

The day began with a keynote “fireside chat” featuring Padma Lakshmi of Top Chef and Taste the Nation. She addressed a sparse but energetic crowd, speaking warmly about her admiration for teachers and the importance of food policy in America—worthy and uncontroversial topics. But most of her remarks centered on her disdain for former President Trump—whom she repeatedly referred to as “the ghoul in the White House”—and the “baby snatchers” she said he employed at Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The loudest applause came when she celebrated recent Democratic victories in New Jersey and New York City.

Keynotes set a tone, and this one was unmistakably political. If the goal of the convention is to help teachers grow as professionals, the opening hour didn’t signal a day focused on improving instruction.

At the 11:15 time slot, I had to make a choice among three concurrent sessions: Creative Ways to Bring Climate Education Alive Across All Disciplines, Standing Up for Transgender and Non-Binary Students, and Don’t Listen to What They Say About Our Urban Schools. The last one caught my attention, given the New Jersey Policy Institute’s deep interest in the ability of urban districts to deliver quality education to their students.

The session began with a forceful challenge to the dominant public narrative about urban schools. The speaker argued that movies like Lean on Me and Dangerous Minds have shaped a false image of city schools as chaotic and failing. Test scores, he said, don’t measure teacher or school quality but simply reflect where poor people live—that education outcomes are determined more by economics and politics than by instruction. He dismissed familiar reform slogans—“no excuses,” “education determines destiny,” and “your ZIP code shouldn’t determine your destiny”—as “lies” that ignore structural realities.

Rather than data, the presentation leaned heavily on student anecdotes—stories from a handful of Camden high schoolers who expressed pride in their schools and frustration with public perceptions. The speaker argued that the “failing schools” narrative is used to justify privatization and redevelopment and said he “hates” the rise of state-driven charter schools, though he wished success for the students who attend them.

It was a compelling talk—part sociology, part sermon—but it also felt detached from the real work of improving schools. Poverty undoubtedly affects outcomes, yet to treat income as destiny is to abandon the very idea that schools can make a difference. Across New Jersey, schools with nearly identical demographics achieve vastly different results. Within those schools, measurable gains appear when leadership focuses on coherent curriculum, additional instructional time, targeted tutoring, and clear expectations. Those realities don’t erase poverty; they prove that practice still matters.

After the session, I made my way to the exhibition hall for a highly publicized presentation titled The Past, Present, and Future of Drag. The presenters spoke courageously about their personal experiences, and the discussion—focused on how to incorporate the story of drag into classroom lessons—was thoughtful and civil.

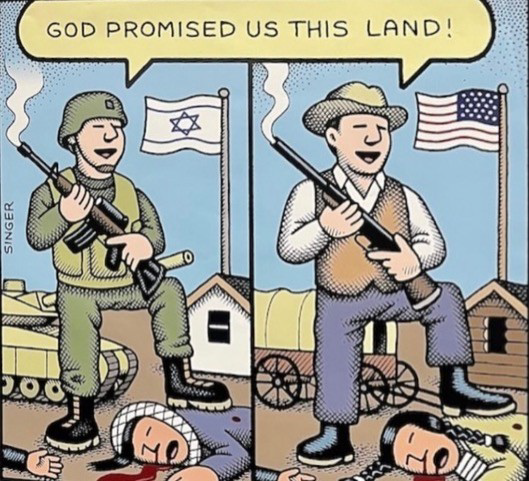

This was followed by a scheduled session titled Teaching Palestine, which was relocated at the last minute. By the time I found the new room, the doors were closed. Later reports indicated that a Jewish attendee had to be escorted out for their own safety. Perhaps it was images like the one shown below, during the session—slides that blurred the line between advocacy and hostility—that pushed things over the edge. It seems the NJEA’s issues with latent antisemitism, once confined to its former magazine editor, may now run deeper within the organization itself…

In fact, the Anti-Defamation League of New York and New Jersey, the American Jewish Coalition, and the Jewish Federations of New Jersey, released a statement condemning the workshop, saying, “at a time of record levels of antisemitism, NJEA platformed content demonizing Israel, Israelis, and Zionism, and recycling classic antisemitic tropes.”

Individually, there was nothing inherently wrong with any of the sessions I attended. A keynote thanking teachers, a discussion about identity and community, a reflection on cultural representation—each, on its own, has some value. But this was a professional development convention sponsored by the state’s largest teachers’ organization, one that claims to focus on strengthening the profession and, through it, improving outcomes for New Jersey’s students.

Of the dozens of sessions offered, I found very few with any clear connection to classroom instruction or measurable student growth. Instead, the agenda leaned heavily toward ideology, self-expression, and political advocacy. While no one should object to open dialogue or diverse perspectives, professional development should, above all, develop professionals. Teachers deserve opportunities that sharpen their craft. Students deserve classrooms where the adults have access to the best tools, research, and training available—and they should be spared any form of political or ideological indoctrination.

If the NJEA truly wants to champion professionalism, it should fill next year’s schedule with sessions that help teachers teach—clear, actionable, replicable ideas that raise achievement. Politics may inspire applause, but only evidence and execution improve learning.